Thomas Thomson expounding Daltons Atomic Theory

from: Thomson, Thomas,

A system of chemistry, 7th ed.

Baldwin & Cradock, London and William Blackwood, Edinburgh, 1831.

INTRODUCTION.

The object of Chemistry, as the science is at present understood, is to determine the constituents of bodies and the laws which regulate the combinations and separations of the elementary particles of matter. All substances are either simple or compound. In simple bodies all the ultimate particles of which they are composed possess precisely the same properties; but from compound bodies at least two distinct kinds of particles may be extracted possessed each of a set of properties peculiarly its own. Thus all the particles which we can extract from a piece of pure iron possess exactly the same properties. Their colour is iron grey, their specfic gravity about 7.8, they are soluble with effervescence in sulphuric acid, forming a light green solution having a sweetish and astringent taste, capable of striking a blue with prussiate of potash, and a black with infusion of nut galls. Iron then, as far as our chemical examination of it is capable of going, is a simple substance. The same observation applies to gold, to silver, and to the diamond.

But saltpetre is a compound substance, for by processes to be afterwards explained, we can extract from it two sets of particles, having each a set of properties peculiarly its own. These are nitric acid and potash. Nitric acid has a peculiar smell, an exceedingly sour taste, reddens vegetable blues, and corrodes and destroys the texture of animal and vegetable substances. When diluted with water it readily dissolves lead, copper, mercury, silver, and many other metals, but does not affect gold or platinum. Potash, on the contrary, is a white substance destitute of smell, but having a hot burning taste, and readily corroding any part of the living body to which it is applied. It converts vegetable blues to green, readily dissolves in water, and readily combines with the different acids, forming salts endowed each with peculiar properties. Thus saltpetre is a compound of nitric acid and potash.

Even nitric acid itself can be resolved into two kinds of matter, endowed each with different properties. These are azote and oxygen; both gases, destitute of smell and invisible and tasteless like common air. But oxygen is heavier than

2 INTRODUCTION.

azote in the proportion of 8 to 7. When a burning body is plunged into oxygen gas it continues to burn with additional splendour; but when plunged into azotic gas it is extinguished. Animals can breathe oxygen gas without inconvenience; but any attempt to breathe azotic gas, if persisted in would be attended with suffocation. Thus nitric acid is a compound of azote and oxygen. In like manner potash is a compound of oxygen, and a metal to which the name of potassium has been given. It is white like silver, lighter than water, and so combustible that when thrown upon water it immediately catches fire, and burns with a red coloured flame.

Thus Saltpetre is a doubly compound body, being composed of nitric acid and potash; each of which constituents is also a compound, the former of azote and oxygen, the latter of potassium and oxygen. We can therefore extract from saltpetre three distinct substances, namely oxygen, azote, and potassium. These three substances cannot be resolved into any other kinds of matter; as far therefore as our knowledge of their constitution goes, they are simple bodies.

All (or almost all) the substances found upon the globe of the earth have been subjected to chemical investigation, with a view to determine which of them are simple, and which compound, and of what constituents the compound bodies consist. The result has been that all the animal and vegetable substances without exception, and by far the greatest number of mineral bodies, are compounds. The simple bodies, of which these compounds are composed, have been carefully examined and their number ascertained. The simple bodies at present known amount to 53; their names are as follows.

1 Oxygen

2 Chlorine

3 Bromine

4 Iodine

5 Fluorine

6 Hydrogen

7 Azote

8 Carbon

9 Boron

10 Silicon

11 Phosphorus

12 Sulphur

13 Selenium

14 Arsenic

15 Antimony

16 Tellurium

17 Chromium

18 Uranium

19 Molybdenum

20 Tungsten

21 Titanium

22 Columbium

23 Potassium

24 Sodium

25 Lithium

26 Calcium

27 Magnesium

28 Barium

29 Strontium

30 Aluminum

31 Glucinum

32 Yttrium

33 Zirconium

34 Thorium

35 Iron

36 Manganese

37 Nickel

INTRODUCTION. 3

38 Cobalt

39 Cerium

40 Zinc

41 Cadmium

42 Lead

43 Tin

44 Bismuth

45 Copper

46 Mercury

47 Silver

48 Gold

49 Platinum

50 Palladium

51 Rhodium

52 Iridium

53 Osmium.

Of these 53 bodies all the substances of nature hitherto examined are composed. The greater number of them are confined to the mineral kingdom. Animal and vegetable bodies are composed of a comparatively small number of simple substances, which, however, from the almost infinite variety in their proportions, give origin to the vast number of bodies which are obtained from the animal, and more especially from the vegetable kingdom.

If we were acquainted with the weight, the size, and the shape of the ultimate particles of these simple bodies, and with the laws which regulate their combinations with each other, the science of chemistry would be in the same state as Astronomy and Mechanics. But unfortunately this is far from being the case. Some little progress has been made in these investigations of late years, and we seem at least to be at last on the road which may ultimately lead to a knowledge of the laws which regulate chemical combinations. But as yet nothing can be considered as definitely fixed or established. Every thing is little better than conjectural. Before proceeding to give an account of the simple bodies, and of the compounds which they form, it will be worth while to lay before the reader the present state of our knowletlge respecting the laws which regulate the combinations of bodies with each other. This will constitute the subject of this introduction.

The opinion at present entertained by Chemists in general, is, that simple substances are aggregates of very minute particles, incapable of farther diminution, and therefore called atoms.* This opinion had been adopted by some of the ancient philosophers, Epicurus, for example; but about the beginning of the eighteenth century, the prevalent belief was, that every kind of matter is capable of infinite division. This subject was treated by Dr. Keill in his introduction to Natural Philosophy, at considerable length, in his third, fourth, and fifth lectures,

* From the Greek particle α and the verb τέμνειν, to cut. The word means literally, incapable of being cut or divided.

4 INTRODUCTION.

where those who are interested in such discussions will find the notions generally entertained at that time on the subject, the mode of answering the objections, and many curious calculations upon the infinite subtility of matter.

What chiefly induced modern chemists to adopt the notion that simple bodies consist of a congeries of atoms, was the observation, that they always combine with each other in definite proportions. For example, iron and sulphur combine in two proportions, and form two sulphurets: the first is a compound of 3.5 iron + 2 sulphur, and the second of 3.5 iron + 4 sulphur. Mr. Dalton, who first drew the attention of chemists to this circumstance, explained it by supposing that bodies are composed of atoms, endowed each with a peculiar weight; that it is these atoms which unite with each other chemically; that the weight of an atom of iron is 3.5, and that of an atom of sulphur 2. The first sulphuret therefore is a compound of 1 atom iron, and 1 atom sulphur, the second of 1 atom iron, and 2 atoms sulphur.

This explanation, in itself very plausible, has been strengthened by some other circumstances.

From the law of the elasticity which prevails in the earth's atmosphere, we know the degrees of rarity corresponding to different elevations from the surface. And if we admit that air has been rarefied so as to sustain only 1/100 of an inch of barometrical pressure, we are entitled to infer that it extends to the height of 40 miles, with properties yet unimpaired by extreme rarefaction. If matter be infinitely divisible, the extent of the atmosphere must be equally infinite. But if air consist of ultimate atoms, no longer divisable, then must the expansion of the medium composed of them cease at that distance where the force of gravity downwards upon a single particle, is equal to the resisting force arising from the repulsive force of the medium.

If the air be composed of indivisible atoms, our atmosphere may be conceived to be a medium of finite extent, and may be peculiar to our planet. But if we adopt the hypothesis of the infinite divisibility of matter, we must suppose the same kind of matter to pervade all space, where it would not be in eqilibrio, unless the sun, the moon, and all the planets possess their respective shares of it condensed around them; in degrees depending on the force of their respective attractions.

It is obvious that the atmosphere of the moon, supposing it to have any, could not be perceived by us. For since the den-

INTRODUCTION. 5

sity of an atmosphere of infinite divisibility at her surface would depend upon the force of her gravitation at that point, it would not be greater than that of our atmosphere is, when the earth's attraction is equal to that of the moon at her surface. Now, this takes place at about 5000 miles from the earth's surface, a height at which our atmosphere, supposing it to extend so far, would be quite insensible.

But since Jupiter is fully 309 times greater than the earth, the distance at which his action is equal to gravity, must be as √309, or about 17.6 times the earth's radius. And since his diameter is nearly 11 times greater than that of the earth, 17.6/11 = 1.6 times his own radius will be the distance from his centre, at which an atmosphere equal to our own, should occasion a refraction exceeding one degree. To the 4th satellite this distance would subtend an angle of about 3° 37', so that an increase of density to 3½ times our common atmosphere, would be more than sufficient to render the 4th satellite visible to us when behind the centre of the planet, and consequently to make it appear on both sides at the same time. It is needless to say that this does not happen; and that the approach of the satellites, instead of being retarded by refraction, is regular till they appear in actual contact showing that there is not that extent of atmosphere which Jupiter should attract to himself, from an infinitely divisible medium filling space.

If the mass of the sun be considered as 330,000 to that of the earth, the distance at which his force is equal to gravitation, will be √330.000 or about 575 times the earth's radius. And if his radius be 111.5 times that of the earth, then this distance will be 575/111.5 = 5.15 times the sun's radius. But Dr. Wollaston has shown by the phenomena attending the passage of Venus very near the sun on the 23d May, 1821, that the sun has no sensible atmosphere. For the apparent and calculated place of that planet were the same when the planet was only 53' 15" from the sun's centre. M. Vidal of Montpellier, observed Venus on the 30th May, 1805, when her distance from the centre of the sun was about 46' of space, and the apparent and calculated positions of that planet corresponded. These observations leave no doubt that the sun has no sensible atmosphere, and of course are inconsistent with the notion of the infinite divisibility of the matter of our atmosphere.

* Wollaston; Phil. Trans. 1822, p. 89.

INTRODUCTION. 6

The conversion of solid and fluid substances into vapour is occasioned by the accumulation of heat in them, which by its elasticity overcomes the action of gravitation, and of cohesive attractions, and causes the particles to separate indefinitely from each other. But if the ultimate particles of bodies be atoms, incapable of farther division or diminution, it is obvious that there must be a limit to vaporisation; and that no vapour will be formed whenever the action of gravitation or cohesion or both is greater than that of heat. This has been very well illustrated by Mr. Faraday in his paper on the existence of a limit to vaporization.* It may be worth while to mention a few of the most remarkable illustrations of the truth of this opinion.

When some clean mercury is put into the bottom of a clean dry bottle, a piece of gold leaf attached to the under part of the stopper by which it is closed, and the whole left for some months at a temperature between 60° and 80°, the gold leaf will be found whitened by amalgamation, in consequence of the vapour which rises from the mercury beneath. Mr. Faraday tried this process in the winter of 1824-5; but could not succeed. Showing that the elasticity of the vapour of mercury at that cold temperature was less than the force of gravity upon it, and that consequently the mercury at that time was fixed.

Davy, in his experiments on the electrical phenomena exhibited in vacuo, found that when the temperature of the vacuum above mercury was lowered to 20°, no farther diminution took place, though the temperature was still farther lowered, even as far as –20°*. The reason doubtless was, that at 20° mercury ceased even in vacuo to give out vapour.

Concentrated sulphuric acid boils at a temperature rather higher than 600°. Signor Bellani placed a thin plate of zinc at the upper part of a closed bottle, at the bottom of which was some sulphuric acid. No action took place in two years, the zinc remaining as bright as at first; showing that none of the acid is converted into vapour at common temperatures.

Thus the phenomena of evaporation, as well as the finite extent of our atmosphere, all tend to prove that matter is not infinitely divisible, but that its ultimate particles consist of atoms incapable of any further division or diminution. Let us see how far our knowledge extends relative to these ultimate atoms.

* Phil. Trans. 1826, p. 484.

INTRODUCTION. 7

1. The size of these ultimate atoms is minute to a degree, of which our limited imginations can form no conception. A few illustrations will render this sufficiently evident.

Gold leaf is formed by beating fine gold between folds of parchment and vellum, and finally between prepared ox gut, known by the name of gold beater's leaf. And it is beaten so thin, that Mr. Boyle found that 50.7 square inches of it weighed only one grain. Now, the 1000th part of a linear inch is easily visible through a common pocket glass. A square inch therefore is divisible into a million of parts, visible through a common microscope. Hence it follows that when gold is reduced to the thinness of gold leaf, 1/50,700,000th of a grain of it may be distinguished by the eye. But the gold that covers silver wire is much thinner than gold leaf. Reaumur has shown that 1 grain of gold, of the thinness which it is upon gilt silver wire, will cover an area of 1400 square inches. It is plain therefore, that 1/1,400,000,000th of a grain of gold may be seen through a common glass. But small as this particle is, we have no reason for believing that it does not constitute a considerable number of atoms.*

I dissolved 1 grain of dry nitrate of lead in 500,000 grains of water, and after having agitated the solution passed through it a current of sulphuretted hydrogen gas. The whole liquid became sensibly discoloured. Now, we may consider a grain of water as being about equal to a drop of that liquid. And a drop may be easily so spread out as to cover a square inch of surface. And under an ordinary microscope the 1/1,000,000 of a square inch may be distinguished by the eye. The water therefore could be divided into 500,000,000,000 parts, every one of which, contained some lead united to sulphur. But the lead in a grain of nitrate of lead weighs only 0.62 gr. It is obvious therefore, that an atom of lead cannot weigh more than 1/510.000.000.000th of a grain. While the atom of sulphur (for the lead was in combination with sulphur, which rendered it visible) cannot weigh more than 1/2015,000,000,000 of a grain.

The size of these very minute quantities of matter might easily be computed; but it would be so small as to render it impossible for us to form any adequate estimate of it. For example, the bulk of the portion of lead which may be ren-

* Those who are curious to see a minute account of the mode of making gold leaf, and gilt wire, will find ample information by consulting Reaumur. Mem. Paris, 1713. p. 199. And Lewis's Philosophical Commerce, p. 44.

8 INTRODUCTION.

dered visible by the process above described, would be only 1/888,492,000,000,000th of a cubic inch.

2. But notwithstanding the extreme minuteness of the size of the ultimate atoms of bodies, chemists have succeeded in determining that each of them has a specific weight, and in fixing the ratios of their respective weights with a considerable approximation to accuracy. The method of proceeding has been to determine when two bodies unite with each other, the weight of each which enters into the combination. For as only the ultimate atoms of bodies combine with each other, it is clear that the weight of each constituent of the compound will be in the ratio of the weight of the ultimate particles, or atoms of the respective bodies. When bodies unite only in one proportion, it is natural to infer that the compound consists ultimately of one atom of one body, united to one atom of the other. Thus, lead and sulphur are usually found combined in one proportion, constituting galena or common sulphuret of lead. This compound consists of 13 parts, by weight of lead united to 2 of sulphur. Hence, it is natural to infer that the weight of an atom of lead is to that of an atom of sulphur, as 13 to 2. In like manner there is only one sulphuret of bismuth known, composed of 9 parts by weight of bismuth, and 2 of sulphur. From this we may infer that the atom of bismuth is to the atom of sulphur as 9 to 2. Now 2 representing the weight of the atom of sulphur in both compounds, it is clear that the ratio of the atom of lead to the atom of bismuth must be that of 13 to 9.

Having thus determined the atomic weight of sulphur to be 2, we may consider the compounds of sulphur and oxygen, which are no fewer than 5. The names and constituents (by weight) of these respective compounds are as follows.

| Sulphur. | Oxygen. | ||

| Subsulphurous acid | 2 | + | 1 |

| Hyposulphurous acid | 4 | + | 1 |

| Sulphurous acid | 2 | + | 2 |

| Sulphuric acid | 2 | + | 3 |

| Hyposulphuric acid | 4 | + | 5 |

If 2 denote the weight of an atom of sulphur, it is obvious that hyposulphurous acid and hyposulphuric acid contain each 2 atoms of sulphur. There can be only 1 atom of oxygen in hyposulphurous and subsulphurous acids. Sulphurous acid

INTRODUCTION. 9

contains 2 atoms of oxygen, and sulphuric acid 3 atoms of oxygen, combined each with one atom of sulphur. Hyposulphuric acid is a compound of 2 atoms of sulphur, and 5 atoms of oxygen, or it is the same thing as if it consisted of a particle of sulphurous, and a particle of sulphuric acid united together. Thus it appears that if 2 denote the weight of an atom of sulphur, 1 will denote the weight of an atom of oxygen.

In many cases it is not easy to fix upon the true number denoting the atomic weight of a body. We can always infer that the weight of one body that enters into combination with another, either denotes the atomic weight of the body, or at least a multiple or submultiple of that weight; but, in some cases it may he very difficult to determine which of the three. Thus, for example, we have two compounds of mercury and oxygen, the constituents of which by weight are as follows.

| Mercury. | Oxygen. | ||

| Black oxide | 25 | + | 1 |

| Red oxide | 25 | + | 2 |

We might consider the atom of mercury to be 25. On that supposition the black oxide would be a compound of 1 atom mercury + 1 atom oxygen, and the red oxide of 1 atom mercury + 2 atoms oxygen.

But we might also consider the atom of mercury as only 12.5 or the half of 25. In that case the red oxide would he a compound of one atom of mercury, and one atom of oxygen; and the black oxide of 2 atoms of mercury, and one atom of oxygen. There is nothing in these compounds that can determine which of these views is the right one. Both oxides are capable of combining with acids, and of forming salts. The red oxide is the most permanent, and intimate combination; but the black is always first formed when we attempt to combine mercury with oxygen. In such cases as this we are left to conjecture or analogy to assist us in deciding what number should be taken to denote the true atomic weight of the body. We see that the atom of mercury weighs either 25 or the half of 25; but which of the two it might in the present state of our knowledge be impossible to determine. In such a case we may be allowed to refer to analogy, to enable us to decide the point. It was first observed by Dulong and Petit, that when the atomic weight of a body is multiplied into its specific heat

10 INTRODUCTION.

the product is a constant quantity. And I have shown in my treatise on Heat that this product is always 0.376. Therefore, if we divide 0.376 by the number denoting the specific heat of mercury, the quotient should be the atomic weight of that body. But the specific heat of mercury is 0.03, and 0.376/0.03 = 12.52. This circumstance furnishes a reason for considering the true atomic weight of mercury to be 12.5.

In like manner we have two combinations of copper and oxygen, the constituents of which are as follows.

| Copper. | Oxygen. | ||

| Red oxide of copper | 8 | + | 1 |

| Black oxide | 8 | + | 2 |

We might consider the red oxide as a compound of 1 atom copper, and 1 atom oxgen, and the black oxide as a compound of 1 atom copper, and 2 atoms oxygen. In that case the atom of copper would weigh 8. But we might represent the constituents of these oxides also, thus –

| Copper. | Oxygen. | ||

| Red oxide | 8 | + | 1 |

| Black oxide | 4 | + | 1 |

According to this view of the compositions, the black oxide is compound of one atom copper, and 1 atom oxygen; and the red oxide of 2 atoms copper, and 1 atom oxygen, and the atomic weight of copper wouldd be 4. Thus we are left uncertain whether the atom of copper be 4 or 8.

If we examine the nature of these oxides in order to assist our views, we find that the black oxide is the most intimate compound, resembling in this circumstance the red oxide of mercury. We find that it constitutes the basis of all the cupreous salts, and that if its atomic weight be reckoned 5, the salts of copper are compounds of one atom acid + one atom base. But if we make its atomic weight 10, all the cupreous salts contain 2 atoms of acid united with one atom of base, – a peculiarity which would distiuguish them from all the other genera of salts. Finally the specific heat of copper has been determined to he 0.0949. Now, if we divide 0.376 by 0.0949 the quotient is 3.962. All these circumstances seem to leave no ground for hesitation, in preferring 4 to 8, as the true atomic weight of copper. If the specific heat of copper were 0.094

INTRODUCTION. 11

then .376/.094 = 4. Now the difference between 0.094 and 0.0949 is greatly within the limits of error to which the determination of the specific heat of a body is liable.

But there are some cases in which it is very difficult to decide what the true atomic weight of a body is, even when assisted by all the analogical considerations to which we can have recourse. Thus oxygen and hydrogen unite in two proportions forming two compounds, the constituents of which are as follows.

| Hydrogen. | Oxygen. | ||

| Water | 0.125 | + | 1 |

| Deutoxide of hydrogen | 0.125 | + | 2 |

If we consider water as a compound of 1 atom oxygen, and 1 atom hydrogen, the weight of an atom of hydrogen will be 0.125, or the eighth part of the weight of an atom of oxygen. But we might view the constitution of these compounds in this way.

| Hydrogen. | Oxygen. | ||

| Water | 0.125 | + | 1 |

| Deutoxide of hydrogen | 0.0625 | + | 1 |

The deutoxide of hydrogen, according to this view of the compounds, would consist of one atom of hydrogen, united to one atom of oxygen, and water of two atoms of hydrogen united to one atom of oxygen. Thus the atom of hydrogen may either weigh 0.125 or 0.0625, which is the half of the former number.

If we have recourse to analogy to guide us in this difficulty we find water is by far the most intimate of the two combinations, and that it is always formed when oxygen and hydrogen enter directly into combination. We find that water combines definitely with various bodies, both acid and alkaline; but without neutralizing their peculiar qualities. But that deutoxide of hydrogen enters into no known combination. These analogies lead to the inference that the atom of hydrogen weighs 0.125.

But oxygen and hydrogen when in a separate state are both gaseous; and if we suppose them to enter directly into combination, and form the two compounds, these compounds will be composed as follows.

| Oxygen. | Hydrogen. | ||

| Water | 1 volume | + | 2 volumes |

| Deutoxide of hydrogen | 1 | + | 1 |

Now it is more simple to consider the compound of 1 volume of each constituent, as composed of an atom of each, than to

12 INTRODUCTION.

reckon 1 volume of oxygen, and 2 volumes of hydrogen, as equivalent each to an atom. This view of the subject would lead to the opinion that the atom of hydrogen weighs only 0.0625.

In this dilemma we may have recourse to the specific heat of hydrogen gas, which will give us data, from which the true atomic weight of hydrogen is most likely to be determined. According to the experiments of Delaroche and Berard, the specific heat of hydrogen gas referred to water is 3.2936. Now 0.576/3.2936 = 0.114 – a number much nearer 0.125, than to 0.0625. The specific heat then naturally leads us to determine in favour of 0.125 as the true atomic weight of hydrogen.

The following table exhibits the atomic weights of the simple bodies determined from the best data with which I am acquainted.

| Atomic Weight. | |

| Oxygen | 1 |

| Chlorine | 4.5 |

| Bromine | 10 |

| Iodine | 15.75 |

| __________________ | _________ |

| Hydrogen | 0.125 |

| Azote | 1.75 |

| Carbon | 075 |

| Boron | 1 |

| Silicon | 1 |

| Phosphorus | 1.5 |

| Sulphur | 2 |

| Selenium | 5 |

| Arsenic | 4.75 |

| Antimony | 5.5 |

| Tellurium | 4 |

| Chromium | 4 |

| Uranium | 26 |

| Molybdenum | 6 |

| Tungsten | 15.75 |

| Titanium | 4 |

| Columbium | 18 |

| __________________ | _________ |

| Potassium | 5 |

| Sodium | 3 |

| Lithium | 0.75 |

| Calcium | 2.5 |

| Magnesium | 1.5 |

| Barium | 8.5 |

| Strontium | 5.5 |

| Aluminum | 1.25 |

| Glucinum | 2.25 |

| Yttrium | 4.25 |

| Zirconium | 5 |

| Thorinum | 7.5 |

| Iron | 3.5 |

| Manganese | 3.5 |

| Nickel | 3.25 |

| Cobalt | 3.25 |

| Cerium | 6.25 |

| Zinc | 4.25 |

| Cadmium | 7 |

| Lead | 13 |

| Tin | 7.25 |

| Bismuth | 9 |

| Copper | 4 |

| Mercury | 12.5 |

| Silver | 13.75 |

| Gold | 25 |

| Platinum | 12 |

| Palladium | 6.75 |

| Rhodium | 6.75 |

| Iridium | 12.25 |

| Osmium | 12.5 |

INTRODUCTION. 13

It is not unlikely that some of these numbers may be twice as high as they ought to be.

3. After determining the ratios which exist between the weights of the atoms of simple bodies, the next particular which deserves investigation, is the comparative size of these atoms. Their absolute bulk we have seen is small to a degree that exceeds the utmost stretch of the imagination. But from the great differences which exist between the specific gravities of bodies, there is reason to suspect that considerable differences must exist between the relative sizes of the atoms. Five of the simple bodies are gaseous. Now, if we were to admit that the same volume of every gas contained the same number of atoms, then the atomic weight of a gaseous body divided by its specific gravity, would give us the ratio of the volume. We have no reason for supposing that equal volumes of azote, hydrogen and chlorine, do not contain the same number of atoms each. But it is obvious that if the weight of an atom of hydrogen be 0.125, or, in other words, if water be a compound of one atom of oxygen and one atom of hydrogen, (since that liquid is a compound of 1 volume of oxygen, and two volumes of hydrogen,) a volume of oxygen must contain twice as many atoms as a volume of hydrogen.

The specific gravities of these gases, referred to oxygen as unity, are as follows.

| Sp. gravity. | Atomic weights. | |

| Oxygen | 1 | 1 |

| Hydrogen | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| Azotic | 0.875 | 1.75 |

| Chlorine | 3.25 | 4.5 |

Dividing these atomic weights by the corresponding specific gravities, we obtain for the volumes,

| Oxygen | 2 |

| Hydrogen | 2 |

| Azote | 2 |

| Chlorine | 2 |

The volumes of hydrogen, azote, and chlorine are all equal. That of oxygen would appear at first sight to be only half that of the others, or unity. But if we recollect that half a volume of it contains as many atoms as a whole volume of the other gases it is obvious that we must consider its specific gravity

14 INTRODUCTION.

not 1, but only 0.5; and 1/0.5 = 2. So that the volume of an atom of oxygen is of the same size as that of the other three. With respect to solid and liquid bodies there is some uncertainty of the relative number of atoms contained in a given volume of each. We have no evidence that the number of atoms in the same volume of each is not the same, and that the intervals in these solid and liquid bodies not occupied by matter, does not depend upon the relative size of the atoms. But we can produce no evidence whatever in favour of that opinion. The following table exhibits the relative volumes of the atoms of different bodies determined by dividing the atomic weight of each body by its specific gravity.

| Volume of the atom. | ||

| Carbon | 1 | |

| Nickel | } | 1.75 |

| Cobalt | ||

| Manganese | } | 2 |

| Copper | ||

| Iron | ||

| Platinum | } | 2.6 |

| Palladium | ||

| Zinc | 2.75 | |

| Rhodium | } | 3 |

| Tellurium | ||

| Chromium | ||

| Molybdenum | 3.25 | |

| Silica | } | 3.5 |

| Titanium | ||

| Cadmium | 3.75 | |

| Arsenic | } | 4 |

| Phosphorus | ||

| Antimony | ||

| Tungsten | } | 4.25 |

| Bismuth | ||

| Mercury | ||

| Tin | } | 4.66 |

| Sulphur | ||

| Selenium | } | 5.4 |

| Lead | ||

| Gold | } | 6 |

| Silver | ||

| Osmium | ||

| Oxygen | } | 9.33 |

| Hydrogen | ||

| Azote | ||

| Chlorine | ||

| Uranium | 13.5 | |

| Columbium | } | 14 |

| Sodium | ||

| Bromine | 15.75 | |

| Iodine | 24 | |

| Potassium | 27 |

From this table we see (if any confidence can be put in the mode of calculation,) that the size of the atoms of bodies differs considerably from each other – and that carbon has the smallest, and potassium the greatest bulk of all atoms hitherto determined.

The atoms of manganese, iron, and copper, have the same size; and it is just double that of carbon. So that nature appears to have succeeded in the difficult mathematical problem of doubling a cube. Phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony, have also the same size, and it is just double that of iron, and quadruple that of carbon.

Rhodium, tellurium, and chromium constitute another group,

INTRODUCTION. 15

whose atoms have the same volume. The size of gold, silver, and osmium, is twice as great as that of these bodies. The size of the simple gaseous atoms is a little more than thrice that of chromium.

4. We have no means of forming any conclusions respecting the shape of the atoms of bodies which can be depended on. It has been concluded by some that the atoms of different bodies differ in their shape as well as in their weight and size. It has even been conjectured that the regular crystalline shape of bodies is owing to the regular shape of their atoms. And Hauy thought that the shape of the ultimate particles of bodies could be determined by cutting off slices from crytals parallel to all their faces, till the shape ceased to alter. Thus if we continue ever so long cutting off slices parallel to the faces of a cube or tetrahedron, what remains will always continue to be a cube or a tetrahedron; and if we dissect an octahedron ever so long, we shall always resolve it into octahedrons and tetrahedrons. But this could not give us the true shape, except on the supposition of the infinite divisility of matter.

Were we to suppose all the atoms of matter to be spheres, it is plain that all the different crystalline shapes conceivable, might be formed by the aggregation of such spheres. Four of them placed in the angles of a tetrahedron, or eight of them at the corners of a very small cube supposed existing in space, would form the rudiments of the tetrahedron or cube. Six cubes applied to the respective faces of the cube, would form the octahedron. If the atoms of bodies were attached to each other without any intervening space between them, then some conclusions might be drawn from the shape of the crystals which they form; but as this is not the case, as the empty spaces existing in every body are probably considerable, and often certainly far exceed the portion of matter to which the shape is owing, it is clear that no legitimate consequences can be drawn, relative to the shape of the atoms of matter, from the figure which they produce when they cohere together constituting a sensible mass of matter. Accordingly, various opinions have been advanced upon this subject. Some suppose that the atoms of all bodies are spheres, or, at least rendered spherical by the atmosphere of heat collected around them. Dr. Wollaston was of opinion, that the regular figures of bodies could be best explained by the supposing the atoms

16 INTRODUCTION.

of bodies to be spheres, or sometimes oblong spheroids.* This also was the opinion of Dr. Hooke.

But there are some circumstances which seem scarcely consistent with this supposition, or at least do not seem easily explicable upon it, or deducible from it. The most important of these, is the fact, that several bodies are capable of crystallizing in two different and incompatible forms.

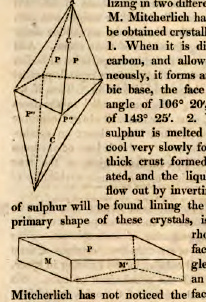

M. Mitcherlich has shown that sulphur may be obtained crystallized in two different ways.

1. When it is dissolved in bisulphuret of carbon, and allowed to crystallize spontaneously, it forms an octahedron with a rhombic base, the face P inclining on P at an angle of 106° 20', and P on P' at an angle of 143° 25'.

2. When a large quantity of sulphur is melted in a pot, and allowed to cool very slowly for four or five hours, if the thick crust formed on the surface be perforated, and idle liquid sulphur be allowed to flow out by inverting the pot, large crystals of sulphur will be found lining the inside of the pot. The primary shape of these crystals, is an oblique prism with rhombic bases, in which the face M makes on M' an angle of 90° 32', and P on M an angle of 85° 54'½.† Mitcherlich has not noticed the fact with regard to sulphur; but in general, when a substance assumes two different and incompatible shapes, the specific gravity and the hardness are found to differ as well as the shape. The most simple explanation of these two shapes of sulphur, is to admit that the atom of sulphur has a peculiar shape, and that when the atoms attach themselves to each other by certain faces, one of the primary forms is produced, and another primary form when they cohere by other faces. The shape of the atom may be such, that only two different kinds of faces exist in it. When the aggregation takes place by one set of faces, the intervals between the atoms may be smaler than when the other faces cohere. This would occasion a greater specific gravity and a greater degree of hardess. Sulphur is not the

M. Mitcherlich has shown that sulphur may be obtained crystallized in two different ways.

1. When it is dissolved in bisulphuret of carbon, and allowed to crystallize spontaneously, it forms an octahedron with a rhombic base, the face P inclining on P at an angle of 106° 20', and P on P' at an angle of 143° 25'.

2. When a large quantity of sulphur is melted in a pot, and allowed to cool very slowly for four or five hours, if the thick crust formed on the surface be perforated, and idle liquid sulphur be allowed to flow out by inverting the pot, large crystals of sulphur will be found lining the inside of the pot. The primary shape of these crystals, is an oblique prism with rhombic bases, in which the face M makes on M' an angle of 90° 32', and P on M an angle of 85° 54'½.† Mitcherlich has not noticed the fact with regard to sulphur; but in general, when a substance assumes two different and incompatible shapes, the specific gravity and the hardness are found to differ as well as the shape. The most simple explanation of these two shapes of sulphur, is to admit that the atom of sulphur has a peculiar shape, and that when the atoms attach themselves to each other by certain faces, one of the primary forms is produced, and another primary form when they cohere by other faces. The shape of the atom may be such, that only two different kinds of faces exist in it. When the aggregation takes place by one set of faces, the intervals between the atoms may be smaler than when the other faces cohere. This would occasion a greater specific gravity and a greater degree of hardess. Sulphur is not the

* Phil, Trans. 1813, p. 51.

† Ann. de Chim et de Phys. xxviii. 264.

INTRODUCTION. 17

only substance which forms two different and incompatible primary forms. Several others are known to exist both among salts and minerals. I may mention the following as examples:

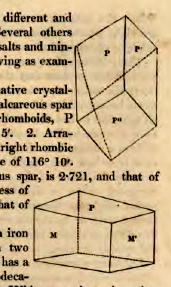

Carbonate of lime is found native crystallized in two distinct forms, 1. Calcareous spar which crystallizes in obtuse rhomboids, P forming on P' an angle of 105° 5', 2. Arragonite, which has the form of a right rhombic prism, M on M' forming an angle of 116° 10'. The specific gravity of calcareous spar, is 2.721, and that of Arragonite 2.931. If the hardness of calcareous spar be reckoned 3, that of Arragonite is 4.

Bisulphuret of iron or common iron pyrites, is found crystallized in two forms: 1. Common iron pyrites has a cube, or perhaps a pentagonal dodecahedron for its primary form. 2. White or cockscomb pyrites has a right rhombic prism for its primary form, M on M' making an angle of 106°. The specific gravity of the former of these varieties, is 4.981, that of the other, 4.678.

The two minerals called zoisite and meionite, are each of them composed of the same constituents, being double salts consisting of two atoms of silicate of alumina, and one atom of silicate of lime; yet the former crystallizes in rhombic prisms, M on M' being 116° 30', and the latter in right prisms with square bases.

Idocrase agrees completely in composition with one of the varieties of garnet, both being double salts composed of one atom of silicate of alumina, and one atom of silicate of lime; yet the former crystallizes in right square prisms, and the latter in rhomboidal dodecahedrons.

Mitcherlich observed that the biphosphate of soda crystallizes sometimes in rectangular octahedrons, having usually a rectangular prism interposed between the pyramids, sometimes in right rhombic prisms, M on M' making an angle of 93° 54'.*

Sulphate of nickel crystallizes in two different forms. When the solution of the salt is neutral, the crystals formed are right rhombic prisms, M on M' forming an angle of about 91° 7'.

* Ann. de Chim. et de Phys. xix. 412 and 414.

18 INTRODUCTION.

When the solution contains an excess of acid, the crystals are right square prisma, exactly similar in shape to those of sulphate of magnesia.*

These 7 examples (and probably others might be adduced) are sufficient to show that the same substances, united in precisely the same proportions, are capable of crystallising in two forms incompatile with each other. Now, if the atoms were all spherical or had all exactly the same form, as was conceived to be the case by Dr. Hooke and Dr. Wollaston, it is not easy to form a notion how these different forms could be assumed, or at least how they should be limited to two. Were we to suppose the shape of the atoms to be triangular prisms, or elongated cubes, or rhomboids, or rhomhoidal prisms, some notion might be formed how the same atoms by uniting by their lateral or by their terminal faces, might form bodies of two different shapes, and differing likewise in their hardness and specific gravity.

But there is another remark of M. Mitcherlich which may ultimately lead to consequences of very great importance, and which accords much better with the notion that the ultimate figure of all atoms is the same, than that each has a peculiar figure of its own. He observed that phosphoric and arsenic acids form with the respective bases, crystals having either the same shape or deviating from each other only by a very small difference in the obliquity of the corresponding faces.

| Thus, biphosphate of potash, | } | crystallize in the very same octahe- |

| Binarseniate of potash, | drons and four-sided rectangular |

prisms, terminated by four-sided pyramids.

| Biphosphate of ammonia, | } | crystallize under the same forms, |

| Binarseniate of ammonia, | but with angles differing a little |

from the corresponding salts of potash.

| Phosphate of soda, | } | crystallize both in right rhombic prisms, |

| Arseniate of soda, | M on M' being an angle of 67° 50' |

in both salts. All the secondary forms of both salts are similar.

| Phosphate of ammonia, | } | crystallize also in right rhombic |

| Arseniate of ammonia. | prisms, M on M in the former |

being 84° 30', and in the latter 85° 54'. The secondary crystals in both salts are also similar.

* See the measurement of these crystals by Mr. Brooks; Annals of Philosophy (2d series), vi. 437. I have analysed both varieties without finding any difference in their composition.

INTRODUCTION. 19

| Biphosphate of barytes, | } | crystallize under the same shape. |

| Binarseniate of barytes, |

He found likewise that the following groups of salts crystallized each in the same shape, and were each identical in their composition – having in each similar crystal the same number of atoms of acid, base, and water.

| Sulphate of manganese | } |

| Sulphate of copper | |

| Sulphate of iron | } |

| Sulphate of cobalt | |

| Sulphate of zinc | } |

| Sulphate of nickel | |

| Sulphate of magnesia. |

The following 13 double salts have also the same shape.

| Ammonio–sulphate of copper Ammonio–sulphate of manganese Ammonio–sulphate of iron Ammonio–sulphate of cobalt Ammonio–sulphate of nickel Ammonio–sulphate of zinc Ammonio–sulphate of magnesia Potash–sulphate of copper Potash–sulphate of iron Potash–sulphate of cobalt Potash–sulphate of nickel Potash–sulphate of zinc Potash–sulphate of magnesia. |

M. Mitcherlich further observed that the crystalline forms of the salts of barytes, strontian, and lead, resemble each other. Thus the nitrate of each of these bodies is a regular octahedron. The sulphate of each is a right rhombic prism, in which M on M form the following angles:

| Sulphate of | barytes | 101° 42' |

| ————— | strontian | 104° |

| ————— | lead | 103° 42' |

The carbonates are also right rhombic prisms, having the following angles:

| Carbonate of | barytes | 118° 30' |

| ————— | strontian | 117° 32' |

| ————— | lead | 117° 18' |

| Arragonite | 116° 10' |

* Kongl. Vetensk. Acad. Handl. 1821, p. 9. Ann. de Chim. et de Phys, xix, 350.

20 INTRODUCTION.

The carbonates of iron and manganese have also the same shape, an obtuse rhomboid; P on P in the former 107°, in the latter 107° 20'.

The carbonates of magnesia, lime, and zinc, have likewise very nearly the same forms, being also obtuse rhomboids. The angle formed by P on P in carbonate of lime, is 105° 5', in carbonate of zinc, 107° 40', as determined by Dr. Wollaston. Carbonate of magnesia has never been measured; but the identity of form is inferred by Mitcherlich from the property which it has of crystallizing indefinitely with carbonate of lime. Potash and ammonia, when combined with the same acid, give salts having the same shape, provided the ammoniacal salt contain two atoms of water.*

From these facts M. Mitcherlich drew as a conclusion, that when two acid bases combine with the same number of atoms of oxygen, and the resulting acids unite with another body in the same proportion, the resulting salts will have the same shape. He found by experiment that when salts can mix with each other, and crystallize jointly in any proportions, they have the same shape.

To substances (whether acids or bases,) which have the property of forming crystals of the same shape when they combine with other bodies, he has given the name of isomorphous. And he is of opinion that the atoms of such bodies have exactly the same shape. The following is a list of the different groups of isomorphous bodies which have been hitherto recognised.

(1.) Lime, magnesia, manganese, oxide of zinc, black oxide of copper, protoxide of iron, protoxide of nickel, protoxide of cobalt

(2.) Potash and ammonia.

(3.) Barytes, strontian, protoxide of lead.

(4.) Titanic acid, peroxide of tin.

(5.) Alumina, peroxide of iron, deutoxide of manganese, protoxide of chromium.

(6.) Phosphorus, arsenic, antimony.

(7.) Phosphoric acid, arsenic acid, antimonic acid.

(8.) Chlorine, bromine, iodine, and fluorine.

(9.) Sulphur, selenium.

This subject, pointing out the identity or similarity of the system of crystallization, which different bodies form when

* Ann de Chim. et de Phys. xiv. 172

INTRODUCTION. 21

they enter into similar combinations, is undoubtedly highly worthy the attention of chemists; and the science lies under considerable obligations to M. Mitcherlich for the very curious facts which he has pointed out. But his general position that atoms of bodies having the same shape, form identical crystals, and that such atoms when they unite with the same number of atoms of oxygen, of base, and of water, form crystals of exactly the same shape, is belied by too many examples, which will readily occur to every chemist and mineralogist, to be admitted as an established fact.

We have no knowledge whatever of the shape of the ultimate atoms of bodies. Mitcherlich infers that phosphorus and arsenic have the same shape, because phosphoric acid and arsenic acid form with bases, crystals either identical, or at least differing from each other by very slight variations in the inclination of the respective faces. But it is not accurate reasoning, first, to infer the identity of form of the simple atoms, from the identity of the crystals formed by the compounds, and then to deduce the identity of form of the compounds from that of the simple atoms.

The only point which M. Mitcherlich has established, and it is a very important one, is, that when two salts have the same crystalline form, they may be mixed together and crystallized in any proportion whatever. M. Beudant made a set of experiments on the power which certain salts have of inducing their own form upon other salts, showing, that a few per cents of sulphate of iron when mixed with sulphate of zinc or sulphate of copper, cause these salts to crystallize in the shape of sulphate of iron.* Dr. Wollaston inferred from the transparency of these crystals, that they could not be mixtures of sulphate of iron with sulphate of zinc, or sulphate of copper, but chemical compounds of the two salts. Because these salts differ so much from each other in their respective powers, that mere mixtures of them could not be transparent.† Mitcherlich confirmed these conclusions of Wollaston by very decisive experiments. He mixed together sulphates of zinc and copper, and by crystallizing the mixed solutions, obtained crystals having the exact shape of sulphate of iron, though they did not contain a particle of this last salt. Sulphate of zinc crystallizes in square prisms, sulphate of copper in very oblique rhombic prisms, and sulphate of iron in right rhombic prisms

* Ann de Chim. et de Phys. iv. 72.

† Annals of Philosophy (1st Series), xi. 283.

22 INTRODUCTION.

of an intermediate obliquity, between that of sulphate of zinc and sulphate of copper. It was obvious that these crystals constituted a double salt, and accordingly it was found that the two salts existed in them in definite proportions.

Sulphates of copper and magnesia, sulphates of copper and nickel, sulphates of manganese and zinc, and sulphates of manganese and magnesia, all unite together, forming double salts having the form of the sulphate of iron. M. Mitcherlich has shown that the water of crystallization of these double salts differs from that of the two constituents, and is the same that exists in sulphate of iron.* Thus it has been proved, that the forms of the salts in Beudant's experiments, was not owing to the influence of sulphate of iron; but to the formation of double salts, the form of whose crystals happened to be the same as that of sulphate of iron.

Mitcherlich showed that the 13 double salts, enumerated in page 19 of this volume, may be mixed and crystallized in any proportion. Carbonates of lime, magnesia, and iron, are found native, mixed in an endless variety of proportions. This law serves to explain an apparent anomaly which occurs in mineralogy. Mineral species consist of simple or double salts united to each other in definite proportions. But there are some mineral species, whose varieties differ so much from each other in their chemical constitutions, that it has been impossible hitherto to establish their constitution upon satisfactory principles. The most remarkable of these minerals species, are the garnet, pyroxene, amphibole, and chrysolite.

The garnet is a well known mineral which crystallizes in rhomboidal dodecahedrons, and has usually a brownish red colour and a great degree of transparency and beauty. It consists essentially of a double anhydrous silicate, and might therefore be subdivided into three species, namely,

| 1. | 1 atom silicate of alumina | } |

| 1 atom silicate of lime | ||

| 2. | 1 atom silicate of alumina | } |

| 1 atom silicate of iron | ||

| 3. | 1 atom silicate of lime | } |

| 1 atom silicate of iron. |

These three salts,

| Silicate of alumina Silicate of lime Silicate of iron, |

* Ann. de Chim. et de Phys. xiv. 180.

INTRODUCTION. 23

are capable, when united, of crystallizing under the same shape. Hence, it happens, that we find minerals crystallizing like garnets containg these three salts in all proportions, or destitute of one of them, and containing the other two only.

Silicate of alumina constitutes the mineral called bucholzite; silicate of lime has not been yet found in the mineral kingdom; but it is often met with among the scori of iron refineries, and frequently crystallized. Silicate of iron constitutes one of the varieties of the mineral called chrysolite or peridot, and is often met in the scoriæ of copper works. Thus the garnet is a compound of bucholzite and silicate of lime, or of chrysolite and bucholzite, or of silicate of lime and chrysolite. And the reason of the great variety which exists in its constitution, is, that these double salts having each the same form, are capable of being mixed in any proportion, without altering the state of the crystallization or the form of the crystal.

Pyroxene is usually a double salt consisting of two bisilicates, which are either of the following:

| Bisilicatc of lime, Bisilicate of magnesia, Bisilicate of iron. |

Mitcherlich has observed crystals having the form of pyroxene in iron scoriæ, and composed entirely of bisilicate of iron.

| Bisilicatc of lime is the mineral usually called table spar. Bisilicate of magnesia is the mineral called picrosmine, Bisilicate of iron is basalt. |

So that pyroxene may be composed of table spar, picrosmine and basalt, united in about any proportions.

The constitution of amphibole and peridot, admits of the same explanation.

If we were to adopt the notion, that the atoms of all bodies are spheres, then the isomorphism noticed by Mitcherlich would admit of an easy explanation. It is obvious, that wherever the bulk of two atoms is the same, one might be substituted for the other without inducing any change in the form of the crystal, of which it is a constituent. Now, upon inspecting the table of the volume of atoms given in page 14 of this volume, it will be seen that arsenic, antimony, and phosphorus, have the same bulk. This accounts for the remarkable isomorphism pointed out in these bodies by Mitcherlich and Rose.*

We have not data to determine the volumes of barytes,

* Poggendorf's Annalen der Physick. xv. 451.

24 INTRODUCTION.

strontian, and oxide of lead. But we will probably find that they have not exactly the same bulk, but that they do not differ much in this respect. Indeed, I have no doubt that isomorphism depends upon the identity of volume, and that the existence of similar suites of crystals, differing a little in their angles, like those exhibited by the compounds of strontian and barytes, are owing to an approach to the same volume in the atoms, without actually reaching identity.

As to the isomorphisms of alumina, peroxide of iron, deutoxide of manganese, and protoxide of chromium, it is inferred solely from double salts, containing each of these bases crystallizing in regular octahedrons; too slender a ground surely to warrant such a conclusion. For the diamond, sal ammoniac, arsenious acid, gold, red oxide of copper, and many other bodies, the isomorphism of which cannot be maintained, crystallize also in regular octahedrons.

Upon the whole, then, the preponderance of evidence is rather on the side of the spherical form of atoms. Though this opinion is attended with difficulties, which in the present state of our knowledge cannot be obviated.

However, even were we to admit that all simple atoms are spheres, it is plain that compound atoms could not be spherical. The particles of water and of muriatic acid must be cylinders, being composed of two equal spheres combined together. Protoxide of lead must be a truncated cone, being formed of two spheres, whose diameters are to each other nearly, as the numbers 2.1 and 1.75. Protoxides of iron and manganese, and black oxide of copper, must be also equal and similar cones, being composed each of two spheres, whose diameters are nearly as the numbers 1.3 and 2.1. It is not improbable that four of these cones may unite together and constitute a cylinder, which may be the state in which these particles aggregate together and constitute crystals.

5. The following are the circumstances which take place, when bodies unite chemically with each other.

(1.) The properties and appearance of the compound differ very much from those of its constituents. Thus, there is no resemblance whatever between water and its two constituents, oxygen and hydrogen. Saltpetre is quite different from nitric acid and potash, of which it is composed. Its taste is cooling and bitter, while that of nitric acid is sour, and that of potash caustic and hot. It is not corrosive, and may even be taken in small quantities into the stomach with impunity, while both

INTRODUCTION. 25

nitric acid and potash are two of the most corrosive substances in nature. It produces no effect on vegetable blues; while nitric acid renders them red, and potash green.

(2.) Bodies (as has been already observed) unite with each other only in definite proportions, which may be represented by numbers.

(3.) When bodies combine chemically, the union is always accompanied by a change of temperature. Sometimes the temperature sinks, but in by far the greatest number of cases it rises. The increase of temperature is usually proportional to the rapidity with which the combination takes place. In many cases the combination is so rapid that combustion is induced.

(4.) When two substances unite chemically, the bulk of the compound is very seldom exactly the same as that of its constituents. In most cases the bulk diminishes, though in some instances it increases.

When 100 cubic inches of absolute alcohol, (sp. gr. 0.796) are mixed with 100 cubic inches of water, the spirit formed instead of 200 cubic inches, measures only 195.8 cubic inches. When tin and copper are melted together, in order to make the metal of cannons, the bulk of the compound is rather more than 1/13th less than that of the two metals before union. Brass, which is a compound of about 8 parts by weight of copper, and 4¼ of zinc, is about 1/20th less bulky than its two constituents were before union.

When a volume of azotic gas unites with half a volume of oxygen gas into protoxide of azote, the bulk of the compound is only 1 volume. So that these two gases by uniting, diminish in volume one-third part. When charcoal is burnt in oxygen gas, the volume of the gas does not increase or diminish, but its weight increases from 1.1111 to 1.5277. So that 1.1111 of oxygen gas has combined with 0.4166 of charcoal, without any increase of volume. The condensation or diminuition in bulk therefore is very considerable.

On the other hand, when copper and gold are melted together, the alloy is more bulky than the constituents were before their union. For example, when 9162/3 cubic inches of gold, and 831/3 of copper are melted together, the compound, instead of occupying the space of only 1000 cubic inches, amounts to 1024 cubic inches, the bulk therefore has increased rather more than 1/42d part.

When a volume of azotic and a volume of oxygen gas combine to form deutoxide of azote, the new compound is still a

26 INTRODUCTION.

gas, and occupies the space of two volumes; so that the two ingredients have combined without altering their former bulk. Yet we are sure that a combination has taken place; for deutoxide of azote possesses quite different properties, from a mere mixture of equal volumes of oxygen and azote; though the specific gravity of such a mixture would be the same as that of deutoxide of azote. We cannot combine oxygen and azote directly with each other into deutoxide of azote. But we can combine directly a volume of hydrogen gas with a volume of chlorine gas into muriatic acid. The combination is instantaneous and accompanied with combustion: yet the bulk of the muriatic acid is precisely the same as that of the two constituents before their union. The same observation is true of hydriodic acid, which is a compound of equal volumes of hydrogen and iodine vapour united together without any change of bulk.

The compounds which the metals form with each other, have been hitherto but superficially examined. Yet some examples are known of two metals which may be smelted together without any alteration of volume, though at the same time they form a chemical union with each other. Thus, M. Kupfer has shown, that when one volume of lead and two volumes of tin are melted together, the bulk of the alloy is just three volumes, so that neither dilation nor contraction have taken place.*

6. When bodies are chemically united with each other, we cannot separate them again by filtration, or any mechanical method whatever. Heat sometimes enables us to produce a separation; but in the greater number of cases this expedient is quite unsuccessful. When a volatile substance is united to another which is more fixed, it cannot be again separated so easily by applying heat, as we might be led to expect from our knowledge of the difference between the volatility of the two constituents. Thus, sulphuric acid does not boil till it be heated above 600°, while water boils at 212°. But if we heat a mixture of sulphuric acid and water, we will be disappointed if we expect that the water can be driven off at 212°. We must raise the heat much higher, before the liquid begins to distil over. And what passes into the receiver is not pure water, but a compound of sulphuric acid and water. It is true indeed, that the acid remaining in the retort is more con-

* Ann. de Chim. et de Phys. xl.

INTRODUCTION. 27

centrated than the liquid which distils over. But after the specific gravity of the acid is raised as high as 1.847, (or when it consists of a combination of 5 acid and 1.125 water by weight,) all farther concentration by heat is at an end. Nothing more passes into the receiver, till the heat is raised to the boiling point of the acid, and then the whole comes over containing the acid and water still united together.

Muriatic acid is a gas, and lime a fixed body, yet when muriatic acid and lime are united into chloride of calcium, no heat that we can apply will separate the two ingredients from each other. We may heat the salt to redness and fuse it to a liquid, but the volatile constituent cannot be separated from the fixed one.

Ammonia is a gaseous body, and nitric acid a liquid. When united they constitute the salt called nitrate of ammonia. No heat which we can apply will separate the ammonia from the nitric acid. When the salt is heated to 300° it melts, and at 450° it undergoes decomposition, being entirely converted into water and protoxide of azote; all traces of both the original constituents of the salt entirely disappearing.

It is therefore impossible in the greater number of cases, to separate the different substances that have been combined, either by mechanical means or by the application of heat. But by multiplying experiments in the way of mixture, a discovery has been made which has been of infinite use to chemists, and has greatly enlarged their power over a great number of different compounds. It has been found, that the addition of some third body to a compound of two ingredients, which are strongly united together by chemical combination, will in many cases dispose them to separate from each other. The third body unites to one of the constituents of the compound, and sets the other constituent at liberty. Thus, if we add potash in the requisite quantity to a compound of sulphuric acid and water, it will combine with the acid and set the water at liberty. A heat of 212° will now cause the water to boil, and it may be distilled over completely, and almost as easily as if the sulphate of potash were not present.

If we dissolve the compound of muriatic acid and lime in water, and add the requisite quantity of potash to the solution, the whole of the lime will be thrown down, and if after separating it by the filter, we evaporate the solution, we obtain a salt composed of muriatic acid and potash, or what is now called chloride of potassium. If, instead of potash, we add the requi-

28 INTRODUCTION.

site quantity of sulphuric acid to the solution of chloride of calcium, the muriatic acid is disengaged and may he obtained in a separate state by distillation, while the lime and sulphuric acid remain united together in the state of sulphate of lime.

The whole art of chemistry consists in forming compounds by uniting different bodies with each other, and in again separating them by the addition of a third body. And he is the best and most skilful chemist, who knows what the third body is which is capable of producing the decompositions that he has in view.

7. What is it that occasions these combinations when bodies are mixed with each other? and how is it that a third body properly chosen, is capable of putting an end to combinations apparently so firm?

When we attempt to explain any curious phenomenon, the method which we take, is to endeavour to show that it may be referred to some principle with which we are already acquainted. But the phenomena of chemistry bear so little resemblance to any thing else with which mankind were familiar, that we need not be surprised that the first attempts to explain them were very unsuccessful. When we are told that an ingenious mechanic has contrived to move an immense mass of rock by the force of one man only, we will not be greatly surprised, if we are at all acquainted with the powers of mechanism. We know the thing to be possible, and that the machine is merely a contrivance for increasing force at the expense of velocity. But when the same rock is moved by a chemist, it is by no means so easy to understand the operation. If we are told, for example, that he mixed a small quantity of saltpetre, charcoal, and sulphur together, laid this mixture under the rock, and having applied a spark of fire to it, the rock was instantly thrown up with great violence and velocity out of its place – we find nothing here that is reducible to the common laws of mechanism – no contrivance for increasing the force at the expense of the velocity – we wonder, we are astonished; but we cannot explain.

It was not till after the time of Lord Bacon that chemistry began to be studied by men who were acquainted with other branches of science. The mechanical powers of bodies being the most familiar of any, mankind have a propensity to employ them in explaining the phenomena of nature. Bacon recommended this sort of reasoning in preference to the language which was common in his time among chemists, and Mr. Boyle

INTRODUCTION. 29

afterwards attempted to introduce it and to support it more fully. If was applied in consequence with so much boldness and so little judgment as to disgust men of real discernment, and to incline them to the notion, that chemical facts could not be explained in a satisfactory manner, by reasoning from mechanical principles.

The paper of Lemery, junior, published in the Memoirs of The French Academy for 1711, entitled Sur les precipitatium chimiques, affords an excellent example of this kind of reasoning. Lemery was a man of great celebrity, and judging from the memoirs which he has left us, he was possessed of considerable merit. He was a member of the Academy of Sciences of Paris, one of the most celebrated scientific institutions in Europe, and his lucubrations on solution and precipitation were thought worthy of publication by that learned body, 24 years after the appearance of Newton's Principia, and 7 years after that of his Optics.

According to Lemery, a fluid which has the power of dissolving a solid body, abounds with sharp and pointed particles, having the forms of needles or wedges, which are agitated in the fluid with a rapid and confused intestine motion. The solid again, has pores of such sizes and shapes as are fitted to the pointed particles of the fluid; these pores are penetrated, and the solid in consequence torn asunder. The reason why potash precipitates marble from its solution in muriatic acid, is, according to Lemery, because its particles are porous and spongy, and by this configuration, and by a confused motion, they take hold of, and break the spiculæ of the acid which held the particles of the lime attached to them. Nitric acid dissolves iron and copper, but not gold, because the two former metals have wider and more numerous pores than gold.

But it is needless to dwell at any great length upon an explanation, which is not only quite gratuitous, but altogether inconsistent with itself, and founded on principles utterly inadequate to explain the phenomena which it undertakes to elucidate. If the pores of iron be wider than those of gold, because it is soluble in nitric acid, while gold is not acted on by that acid; then the pores of gold must be wider than those of iron, because it is dissolved with the greatest facility by mercury, though that metal will not touch iron. Silver dissolves in nitric acid and not gold; but in aqua regia gold dissolves with facility, while silver remains undissolved. We cannot conceive these supposed intestine motions of fluids,

30 INTRODUCTION.

which are utterly insensible, to continue for ever; they must of necessity stop one another, and the particles of the liquid must come to a state of rest.* Yet muriatic acid though kept for ages in a state of rest, would dissolve marble with as much energy as at first. We know, too, that solid bodies are capable of acting upon and dissolving one another, though it is not conceivable that their particles should be in a state of motion. Thus, common salt and snow when mixed together, immediately begin to act upon and mutually to dissolve one another.

These attempts of Lemery and some other similar ones were utterly unsatisfactory – and indeed no chemical theory existed which connected chemistry with the other parts of science, till Newton published the second edition of his Optics, in the year 1717. To the end of this edition he subjoined thirty-one queries, the last of which relates to chemistry. In this query he lays open a view of chemical combination and decomposition, which is altogether his own, which is much more satisfactory, and which makes them appear much more conformable to the rest of natural phenomena than any that had been offered before. Newton had already thirty years before explained the motions and connexion of the heavenly bodies with one another, by showing that they are retained in their orbits by the same power which determines a stone to fall to the ground – a power usually called gravitation or the attraction of gravitation. He conceived that there are other forces or principles of motion in nature, by which certain bodies act or appear to act at sensible distances on one another. This is evidently the case with the attractions and repulsions connected with electricity and magnetism; he suspected that there are still other forces whose sphere of action is still smaller, being confined to the ultimate particles or atoms of bodies – and so small indeed as to escape our senses. These actions or forces he considered as manifest in the attraction and cohesion of polished planes and metals, in what is called capillary attracion, and in the inflection and deflection of light as it passes near the edges of solid bodies.

He suspected that chemical combinations and decompositions depended upon powers somewhat resembling the others. He was of opinion that the ultimate particles or atoms of certain bodies attract each other with an unknown but enormous force, which begins to exert itself only at very minute distances. Hence when such bodies are mixed, the particles of each being

INTRODUCTION. 31

brought within the reqisite distance, this force exerts itself and the bodies unite. The decompositions produced by the addition of a third body lie ascribed to the superiority of the attraction of this third body for one of the constituents of the compound, in consequence of which it unites with that constituent and separates the other which was previously in combination. Thus muriatic acid dissolves marble, because the attractive force between the particles of the acid and those of lime is greater than the force by which the particles of the marble cohere together, and than the force which united the lime in the marble to the carbonic acid. They are therefore separated from each other, and a particle of lime uniting to every particle of muriatic acid, the whole lime, if the quantity of acid be sufficient, is equally diffused through the liquid. When potash is added the lime again falls down, because the potash has a greater attraction for the particles of the acid than the lime has; it therefore unites with the acid and separates the particles of lime, which being disengaged, obey the laws of gravity, and fall to the bottom of the vessel.

These views of Newton made their way into the science very slowly; but before the middle of the last century they seem to have been almost universally adopted. Chemists, however, instead of the term attraction employed by Newton, substituted affinity, first introduced into Chemistry by Dr. Hooke, and caught with avidity by the chemists on the Continent. By chemical affinity then is meant that unknown force which causes the ultimate particles of different bodies to unite together and to remain united. This term is in some respects preferable to attraction. Because this last term naturally suggests the idea that the united bodies are drawn nearer to each other than they were before their union, which is not always the case. For when hydrogen and chlorine unite to form muriatic acid they do not approach nearer each other than they were before their union; and when gold and copper are alloyed together the volume of the compound increases, so that the constituents appear to have receded farther from each other than before they united. Affinity indicating merely the power or the force which produces the union, seems well adapted for the purposes of science.

As soon as the Newtonian notions of affinity were adopted by chemists, they naturally concluded, that, when a compound ab was decomposed by the body c, which combined with b, disengaging a, this was because c had a stronger affinity for b

32 INTRODUCTION.

than a had. Decomposition therefore came to be considered as the measure of the strength of affinity. Dr. Mayow of Oxford seems to have been the first who demonstrated that bodies follow fixed and constant laws in their action on each other. He showed that volatile alkali is separated from all acids by the fixed alkalies, that nitric acid is disenged from saltpetre by sulphuric acid, and that metals are precipitated from acids by potash.*

In the year 1718, M. Geoffroy, senior, thought of arranging bodies in the order in which they separate each other from a given substance.† Bodies thus arranged were considered as exhibiting the order of the affinity of the respective bodies for the substance with which they united; that body being placed highest which had the strongest affinity or was capable of displacing all the others. The rest of the bodies were placed in the order of their affinity.

Geoffroy's tables were necessarily very imperfect. The first great improvement of them was by Gellert, in his Metallurgic Chemistry, first published in 1751. In 1761 a still more extensive table was given to the chemical world by M. Limbourg. Bergman's Dissertations on Elective Attractions (as be termed affinity) was first published in 1775 in the third volume of the Memoirs of the Royal Society of Upsala. This work, afterwards republished by the author in 1783 in the third volume of his Opuscula, appears to have fixed the opinions of chemists in general to his own views of the subject. According to him the affinity of each of the bodies a, b, c, d, &c. for x differs in intensity in such a manner that the intensity of the affinity of each may be expressed by numbers. He was of opinion also that affinity is elective, in consequence of which if a have a greater affinity for x than b has, if we present a to the compound bx, x separates altogether from b and unites to a. Thus barytes has a stronger affinity for sulphuric acid than potash has; therefore if barytes be mixed with a solution of sulphate of potash, the sulphuric acid will leave the potash and combine with the barytes. He examined the alleged exceptions to this general law, and accounted for them with such plausibility as to remove the doubts that had hitherto hung over the subject. Bergman's table of affinities, constructed according to the plan of Geoffroy, was much more copious than any that had preceded

* Mayow de Sal nitro, p. 232.

† Mem. Paris, 1718, p. 202.

INTRODUCTION. 33

it, contaning all the chemical substances at that time known. It consists of 59 columns. At the head of each of which is placed a chemical body, and the column is filled with the names of all the substances which unite with it, each in the order of its affinity. Each column is divided into two compartments by a black line. In the first is exhibited the affinities in the order of the decompositions when the substances are in solution. In the second compartment are exhibited the order of the decompositions when the substances are exposed to a strong heat, as for example by heating them to redness in a crucible. The first of these he called the affinities by the wet way, the second the affinities by the dry way.

Bergman's opinion that affinity is elective, and that the order of affinities is determined by decomposition, continued to be universally admitted by chemists till Berthollet published his Dissertation on Affinity, in the third volume of the Memoirs of the Institute, and his Essay on Chemical Statics in the year 1803. He considered affinity as an attraction existing between the bodies which combine, and an attraction probably similar to that which exists between the planetary bodies. But as those bodies which obey the impulse of affinity are at a very small distance from each other, the strength of their affinity depends not merely upon the quantity of matter which they contain, but likewise upon their shape. Affinity being an attraction, must always produce combination; and as the attraction is analogous to that of the planetary bodies, it follows as a consequence in Berthollet's opinion, that the affinity must increase with the mass of the acting body. Thus though barytes has a stronger affinity for sulphuric acid than potash; yet if we present a great quantity of potash to a small quantity of sulphate of barytes, the potash will separate a portion of the acid.